Monthly Archives: April 2022

Michael Brenner: American Dissent on Ukraine Is Dying in Darkness

Editor’s Note: We are reposting this frank interview and focus more on Prof. Brenner’s own words, while cutting down on the interviewer’s long interruption. For the full conversation please go to the original here.

As the death toll in Russia’s illegal invasion of Ukraine continues to rise, there have only been a handful of Westerners publicly questioning NATO and the West’s role in the conflict. These voices are becoming fewer and further between as a wave of feverish backlash engulfs any dissent on the subject. One of these voices belongs to Professor Michael J. Brenner, a lifelong academic, Professor Emeritus of International Affairs at the University of Pittsburgh and a Fellow of the Center for Transatlantic Relations at SAIS/Johns Hopkins, as well as former Director of the International Relations & Global Studies Program at the University of Texas. Brenner’s credentials also include having worked at the Foreign Service Institute, the U.S. Department of Defense and Westinghouse, and written several books on American foreign policy. From the vantage point of decades of experience and studies, the intellectual regularly shared his thoughts on topics of interest through a mailing list sent to thousands of readers—that is until the response to his Ukraine analysis made him question why he bothered in the first place.

In an email with the subject line “Quittin’ Time,” Brenner recently declared that, aside from having already said his piece on Ukraine, one of the main reasons he sees for giving up on expressing his opinions on the subject is that “it is manifestly obvious that our society is not capable of conducting an honest, logical, reasonably informed discourse on matters of consequence. Instead, we experience fantasy, fabrication, fatuousness and fulmination.” He goes on to decry President Joe Biden’s alarming comments in Poland when he all but revealed that the U.S. is—and perhaps has always been—interested in a Russian regime change.

On this week’s “Scheer Intelligence,” Brenner tells host Robert Scheer how the recent attacks he received—many of a personal, ad hominem nature—were some of the most vitriolic he’s ever experienced. The two discuss how many media narratives completely leave out that the eastward expansion of NATO, among other Western aggressions against Russia, played an important part in fueling the current humanitarian crisis. Corporate media’s “cartoonish” depiction of Russian president Vladimir Putin, adds Brenner, is not only misleading, but dangerous given the nuclear brinkmanship that has ensued. Listen to the full discussion between Brenner and Scheer as they continue to dissent despite living in an America that is seemingly increasingly hostile to any opinion that strays from the official line.

Credits

Host: Robert Scheer

Producer: Joshua Scheer

Transcription: Lucy Berbeo

FULL TRANSCRIPT

RS: Hello, this is Robert Scheer with another edition of Scheer Intelligence, where the intelligence comes from my guests. In this case it’s Michael Brenner, who is a professor of international affairs emeritus at the University of Pittsburgh, a fellow at the Center for Transatlantic Relations at SAIS Johns Hopkins; he’s written a number of important studies, books, academic articles; he’s taught at every place from Stanford to Harvard to MIT and what have you.

But the reason I wanted to talk to Professor Brenner is that he’s been caught in the crosshairs of trying to have a debate about what’s going on in the Ukraine, and the NATO response, the Russian invasion and what have you. And to my mind, I read, I was reading his blog; I found it very interesting. And then he suddenly said, I’m giving up; you cannot have an intelligent discussion. And his description of what’s going on reminded me of the famous Lillian Hellman description of the McCarthy period as “scoundrel times,” which was the title of her book.

So, Professor Brenner, tell us what buzzsaw you ran into when you dared question, as far as I can see, you dared do what you’ve done all your academic life: you raised some serious questions about a foreign policy matter. And then, I don’t know what, you got hit on the head a whole bunch of times. So could you describe it?

MB: Yes, it came only partially as a surprise. I’ve been writing these commentaries and distributing them to a personal list of roughly 5,000 for more than a decade. Some of those persons are abroad, most are in the U.S.; they’re all educated people who’ve been involved one way or another with international affairs, including quite a number who have had experience in and around government or journalism or the world of punditry.

What happened on this occasion was that I had expressed highly skeptical views about what I believe is the fictional storyline and account of what has been happening in Ukraine, back over the past year and most pointedly in regard to the acute crisis that has arisen with the Russian invasion and attack on Ukraine. I received not only an unusually large number of critical replies, but it was the nature of them that was deeply dismaying.

One, many—most of them came from people whom I did know, whom I knew as level-headed, sober minds, engaged and well informed on foreign policy issues and international matters generally. Second, they were highly personalized, and I had rarely been the object of that sort of criticism or attack—sort of ad hominem remarks questioning my patriotism; had I been paid by, you know, by Putin; my motivations, my sanity, et cetera, et cetera.

Third was the extremity of the content of these hostile messages. And the last characteristic, which really stunned me, was that these people bought into—hook, line and sinker—every aspect of the sort of fictional story that has been propagated by the administration, accepted and swallowed whole by the media and our political-intellectual class, which includes many academics and the entire galaxy of Washington think tanks.

And that’s a reinforced impression that had been growing for some time, that this was not just—that to be a critic and a skeptic was not just to engage in a dialogue [unclear], but to place one’s views and one’s thoughts and send them into a void, in effect. A void, because the discourse as it has crystalized is not only uniform in a way, but it is in so many respects senseless, lacking any kind of inner logic, whether you agree with the premises and the formally stated objectives or not.

In effect, this was an intellectual and political nihilism. And one cannot make any contribution to endeavor to correct that simply by conventional means. So I felt for the first time that I was no part of this world, and of course this is also a reflection of trends and attitudes that have become rather pervasive in the country at large, sort of over time. And so beyond simply sort of disagreeing with what the consensus is, I had become totally alienated [unclear] and decided there was no point to it, to going on distributing these things, even though I continue to follow events, think about them, and send some shorter commentaries to close friends. That’s essentially it, Robert.

RS: OK, but let me just say, first of all, I want to thank you for what you did. […]

MB: Well, I mean, it’s the fundamentals. One, it has to do with the nature of the Russian regime, the character of Putin; what Soviet objectives, foreign policy and national security concerns are. I mean, what we’re getting is not only a cartoon caricature, but a portrait of the country and its leadership—and by the way, Putin is not a dictator. He is not all-powerful. The Soviet government is far more complex in its processes of decision-making.

RS: Well, you just said the Soviet government. You mean the Russian government.

MB: Russian government. [overlapping voices] You see, I’ve picked up by osmosis this conflating of Russian and Soviet. I mean, it’s far more complex [unclear]. And he is, Putin himself, an extraordinarily sophisticated thinker. But people don’t bother to read what he writes, or to listen to what he says.

I know, in fact, of no national leader that has laid out in the detail and the precision and the sophistication his view of the world, Russia’s place in it, the character of interstate relations, with the candor and acuity that he has. It’s not a question of whether you believe that that depiction he offers is entirely correct, or the conclusion that he draws from it, with regard to policy. But you are dealing with a person and a regime which in vital respects is the antithesis of the one that is caricatured and almost universally accepted, not only in the Biden administration but in the foreign policy community and the political class, and in general.

And that raises some really basic questions about us, rather than about Russia or about Putin. As you mentioned, the question was: what is it that we’re afraid of? Why do Americans feel so threatened, so anxious? I mean, by contrast in the Cold War—I mean, there was a powerful enemy, ideological, military in some sense, with all the qualifications and nuances [unclear]. But that was the reality then; that was a reality which was, one, the focal point for national leaders who were serious people, and responsible people. Second, that could be used to justify actions highly dubious, but at least could be used to justify, such as our interventions all around the so-called Third World, and even the great, tragic folly of Vietnam.

What is there today that really threatens us? At the horizon, of course, there is China, not Russia; although they now, thanks to our unwitting encouragement, have formed together a formidable bloc. But I mean, even the Chinese challenge is to our supremacy and our hegemony, not to the country directly [unclear]. So the second question is, what is so compelling about the maintenance and the defense of a conception of the United States of America’s providential birth admission in the world that compels us to view people like Putin as being diabolical, and as constituting as grave a threat to America as Stalin and Hitler, whose names constantly crop up, as well as ridiculous phrases like genocide and so on.

So I mean, once again, I think we have to look in the mirror and say, well, we’ve seen—[unclear] the source of our disquiet, and it’s within us; it’s not out there, and it is leading to gross distortions of the way in which we see, we depict and we interpret the world, all across the board. By which I mean geographically and in terms of sort of different arenas and dimensions of international relations. And of course, continuing along this course can only have one endpoint, and that’s disaster of some form or other.

RS: Well, you know, there’s two points that have to be addressed. […] What is going on?

MB: Well, Robert, you’re absolutely right. And that question is the one that should preoccupy us. Because it really cuts deepest into, you know, contemporary America. It’s what contemporary America is. And I think the intellectual tools to be used in trying to interpret it must come from anthropology and psychology at least as much, if not more, than political science or sociology or economics. I truly believe that we are talking about collective psychopathology. And of course, collective psychopathology is what you get in a nihilistic society in which all sort of standard, conventional sort of reference points cease to serve as markers and guideposts on how individuals behave.

And one expression of that is in the erasure of history. We live in the existential—I think in this case the word can be properly used—moment, or week, or month, or year or whatever. So we totally, almost totally forget about the reality of nuclear weapons. I mean, as you said, and you’re absolutely right, in the past, every national leader and every national government that had custody of nuclear weapons came to the conclusion and absorbed the fundamental truth that they served no utilitarian function. And that the overriding, the imperative was to avoid situations not only in which they were used as part of some calculated military strategy, but to avoid situations in which circumstances might develop where, as you said, they would use them because of accident, misjudgment, or something of the sort.

Now, we can no longer assume that. I believe, oddly, in some sense oddly enough, that the people in official positions who must remain most acutely aware of this are the Pentagon. Because they’re the ones who have direct custody of it, and because they study and read about it in the service academy as a whole Cold War sort of history, and the history of weaponry, et cetera.

I’m not suggesting that Joe Biden has sort of sublimated all of this. But he seems to be in a state, hard to describe, in which certainly [unclear] could permit the kind of encounter with the Russians that all his predecessors avoided. Which, in turn, is the kind of encounter where it is conceivable, and certainly not entirely inconceivable, in which nuclear weapons might be somehow resorted to in some uncalculating, you know, way.

And you see that, by the way, in articles published in places like Foreign Affairs and other respectable journals, by defense intellectuals, if you’ll excuse the expression. Whenever I hear the word “defense intellectual,” of course my reaction is to run and hide, but there are people of some note who are writing and talking along these lines, and some of them are neocons of note, like Robert Kagan, Victoria Nuland, sort of husband and partner in crime, and others of that ilk. And so, yes, this is pathological, and therefore really leads us into territory I don’t think we’ve ever been in or experienced before.

RS: So let’s get to the basic, what you feel is the distortion of this situation. […]

MB: Robert, I’ll try to do it in a staccato fashion. One, this crisis, in leading to the Russian invasion, has little to do with Ukraine per se. Certainly not for Washington; for Moscow it’s otherwise. It’s had to do with Russia from the beginning. It’s been the objective of American foreign policy for at least a decade to render Russia weak and unable to assert itself in any manner of speaking in European affairs. We want it marginalized, we want to neuter it, as a power in Europe. And the ability of Putin to reconstitute a Russia that was stable, that also had its own sense of national interest, and a vision of the world different from ours, has been deeply frustrating to the political elites and the foreign policy elites of Washington.

Two, Putin and Russia are not interested in conquest or expansion. Three, Ukraine is prominent to them, not only for historical and cultural reasons, et cetera, but because it is linked to the expansion of NATO and an obvious attempt, as became tangible at the time of the Maidan coup [unclear], that they wished to turn Ukraine into a forward base for NATO. And against the background of Russian history, that is simply intolerable.

I think a point to keep in mind is that—and this relates to what I said a moment ago about policy-making in Moscow—that if one were to place the attitudes and the opinions of Russian leaders on a continuum from hawk to dove, Putin has always been well towards the dovish end of the continuum. In other words, the majority of the most powerful forces in Moscow—and it’s not just the military, it’s not just the oligarchs, it’s all types—the locust of the sentiment has been that Russia is being exploited, taken advantage of; that cooperation will become a part of a European system in which Russia is accepted as a legitimate player is illusory.

So we have to understand that, and I—OK, specifically we’ve gone to the current crisis. The Donbass, and that is not just Russian-speaking but a highly concentrated Russian region of Eastern Ukraine, which tried to separate itself after the Maidan coup—and by the way, Russian speakers in the country as a whole represent 40% of the population. You know, Russians, quite apart from intermarriage and cultural fusion—you know, Russians are not some small, marginal minority in the Ukraine.

OK, quickly down now to the present. I believe there is growing and now totally persuasive evidence that when the Biden people came to office, they made a decision to create a crisis over Donbass to provoke a Russian military reaction, and to use that as the basis for consolidating the West, unifying the West, in a program whose centerpiece was massive economic sanctions, with the aim of tanking the Russian economy and possibly and hopefully leading to a rebellion by the oligarchs that would topple Putin.

Now, no person who really knows Russia believes that it was ever at all plausible. But this was an idea which was very prominent in foreign policy circles in Washington, and certainly the Biden administration, and people like Blinken and Sullivan and Nuland believe in it. And so they set about strengthening even further the Ukrainian army, something we’ve been doing for eight years—Ukrainian army, thanks to our efforts, armaments, training advisors.

And by the way, it is now becoming evident that we might well—probable that we have physically, in the Ukraine now, American special forces, including British special forces and some French special forces. Not only people who have engaged in training missions, but are actually providing some direction, intelligence, et cetera. We’ll see if this ever comes out. And that’s why [unclear] Macron, et cetera, are so desperate about getting the brigades and other special elements trapped in Mariupol out of the city, which they’re not ceding it.

So the idea was you created—and it is now growing evident that in effect, an assault on the Donbass was planned. And that it was in November that the final decision was taken to go ahead with it, and the time set for February. And that is why Joe Biden and other members of the administration could begin to say, with complete confidence, in January that the Russians would be invading Ukraine. Because they knew and committed themselves to a major, a major military attack on the Donbass, and they knew that the Russians would respond. They didn’t know how large a response, how aggressive a response it would be, but they knew there would be a response.

You and listeners might recall Biden saying in February, second week of February that when the Russian invasion comes, if it is small, we’re still going to go ahead with sanctions, but we might have a fight within NATO as to whether to go whole hog. If it is large, there’ll be no problem, everybody will agree on killing Nord Stream II, and taking these unprecedented steps against the Russian Central Bank, et cetera. And he said that because he knew what was planned. And the Russians reached the conclusion about the same time. Well, they certainly understood what the broad game plan was.

And then they crystalized that this was going to happen soon, and the final blow came when the Ukrainians began massive artillery barrages on cities in the Donbass. Now, there had always been exchanges over the past eight years. On February 18, there was a 30-fold increase in the number of artillery shells, five from the Ukrainians into the Donbass, to which the Donbass militias did not retaliate in kind. It peaked on the 21st and continued to the 24th. And this apparently was the last confirmation that the assault would be coming soon, and forced Putin’s hand to preempt by activating plans which no doubt they’d had for some time to invade. I think that has become clear.

Now, this is of course the diametrical opposite of the fictional story that pervades all public discourse. And you can say “all” and only count on the fingers of your hands and toes the number of dissenters, right, that prevails. Now, let’s leave open the question of do you defend Putin’s actions. I, like you, find it very hard to defend, justify, any major military action that has the consequences that this does. Except in absolute, you know, self-defense.

But you know, that’s where we are. And if there had been the Ukrainian assault that was planned on the Donbass, Putin and Russia would have been in real, real trouble, if they limited themselves to resupplying the Donbass militias. Because given the way we had armed and trained the Ukrainians, they really couldn’t withstand them. So that would have been the end of [unclear] subordination of the Russian population and the suppression of Russia’s language, all of which are steps that the Ukrainian government has moved on and has in the work.

RS: You know, what’s at the heart of this really is the denial of anyone else’s nationalism. […]

MB: Yeah, Robert, you’re absolutely right in everything that you say. Of course the world system is being transformed by the formation of this Sino-Russian bloc, which is increasingly incorporating other countries. You know, Iran is already part of it. And you know, we will note that there are only two countries outside the Western world—about which I’m speaking politically and socially, not geographically—who have supported the sanctions: South Korea and Japan. All of Asia, Southwest Asia, Africa and Latin America is not observing them, has not signed on to them. Some are exercising self-restraint and slowing down deliveries of certain things, out of sheer prudence and fear of American retaliation. But we’ve gotten no support from them. So, yeah, the gross underestimation of this, Bob.

Now, in what passes for grand strategy among the American foreign policy community, not just the Biden people, they still—they’ve had a dual hope: one, that they could drive a wedge between Russia and China, an idea they entertain only because they know nothing or have forgotten anything they might have known about each of those countries. Or, second, to in effect neutralize Russia by what we talked about: breaking the Russian economy, maybe getting some regime change, so that they would be a negligible contributor, if at all, to ally with the Chinese. And of course we have failed utterly, because all of those mistaken premises were mistaken.

And this utterly unprecedented hubris, of course, is peculiarly American. I mean, from day one, we’ve always had the faith that we were born in a condition of original virtue, and we were born with some kind of providential mission to lead the world to a better, more enlightened condition. That we were therefore the singular exceptional nation, and that gave us the freedom and the liberty to judge all others. Now, that’s—and we’ve done a lot of good things in part because of that [unclear] dubious things.

But now that’s become so perverted. And as you said, it encourages or justifies the United States setting it up as the judge of what’s legitimate and what isn’t, what government’s legitimate and what isn’t, what policies are legitimate and which aren’t. Which self-defined national interests by other governments we can accept, and which we won’t accept. Of course, this is absurd in its hubris; at the same time it also defies [unclear] logic—Nixon and Kissinger really operated and were able to set aside or sort of, you know, surmount this ideological, philosophical, self-congratulatory faith in American unique prowess and legitimacy, based on strictly practical grounds.

And currently, though, we don’t exercise restraint based either upon a certain political-ideological humility, nor on realism grounds. And that’s why I say we’re living in a world of fantasy—a fantasy which clearly serves some vital psychological needs of the country of America, and especially of its political elites. Because they are the people who are supposed to have taken on the custodial responsibility for the welfare of the country and its people, and that requires maintaining a certain perspective and distance on who we are, on what we can and cannot do, of reality testing even the most basic and fundamental of American premises. And now we don’t do any of that.

And in that sense, I do believe it’s fair to say that we have been betrayed by our political elites, and I use that term, you know, fairly broadly. The susceptibility to propaganda, the susceptibility to allowing the popular mindset to be set the way it’s going on now, in giving in to hysterical impulse, means that yeah, there’s something wrong with society and culture as a whole. But even saying that is up to your political leaders and elites to protect you from that, to protect the populace from that, and to protect themselves from falling prey to similar fantasies and irrationalities, and instead we see just the opposite.

RS: You know, one final point, and you’ve been very generous with your time. […] It’s kind of the Roman empire gone nuts.

MB: You’re absolutely right, Robert. And it is China which we look at over our shoulder. And I mean, you could argue in a number of respects—if you look at Chinese history, they have never been terribly interested in conquering other societies, nor in governing alien peoples. Their expansion, such that it was, was to the west and to the north, and was an extension of their millennia-long wars with the marauding tribes of central Asia, and dealing with that constant threat. And you know, those Central Asian barbarians succeeded four times in breaking through and in bringing them central authority in Asia.

So they’ve never been in the conquering business. Two, yes—so it’s easy enough and convenient enough to conflate China’s growing military capabilities with its economic prowess, and the fact that its whole system, in every respect, whatever you want to call it—state capitalism, ideological overlay, whatever—and whatever it turns out to be, to crystalize, it is going to be different from what we’ve seen before. And that is very threatening. Because it calls into question our self-definition as being in effect the natural culmination point of human progress and development. And suddenly we’re not; and second, the guy who’s taken another path might very well—is certainly going to be in a position to challenge our dominance politically, in terms of social philosophy, economically, and secondarily, militarily.

And there is simply—you know, we won’t censor—there is simply no place in the American conception of what’s real and natural for a United States that is not number one. And I think that’s ultimately what drives this anxiety and paranoia about China, and that is why we have not seriously entertained the alternative. Which is, you develop a dialogue with the Chinese that’s going to take years, that will be continual, in which you try to work out the terms of a relationship, about a world which will be different from the one we’re in now, but will certainly satisfy our basic interests and concerns as well as China’s. To agree on rules of the road, to carve out areas of convergence as well. You know, a dialogue of civilizations.

That’s the kind of thing which Chas Freeman, one of the most distinguished diplomats, and who was the interpreter as a young man for Nixon when he went to Beijing. And he’s been writing and saying this since his retirement 10, 12 years ago, and the man is ostracized, he is shunned, he is invited almost nowhere to speak, nobody asks him to write an op-ed piece. As far as the New York Times and the Washington Post and the mainstream media, he doesn’t exist.

RS: Who is that you’re referring to?

MB: Charles Freeman. And he still writes, and incredibly intelligent, acute, sophisticated, I mean, by orders of magnitude superior to the kinds of clowns who are making our China policy today. And recently published a breathtaking long essay on the nature and character of diplomacy. So he’s the kind of person who could, you know, be involved in and help to shape the kind of dialogue I’m talking about. But these people don’t seem to exist. Those that have any potential like that are marginalized, right.

And instead we’ve taken this sort of simplistic path of saying the other guy is the enemy, he’s the bad guy, and we’re going to confront him across the board. And I think this is going to lead to, sooner or later, to confrontation and crisis, probably over Taiwan, which will be the equivalent of the Cuban missile crisis, and hope that we survive it, because we’re going to lose a conventional war if we choose to defend Taiwan. And everybody who knows China says the Chinese leadership is watching the Ukraine affair very closely, and thinking to themselves, ah, maybe Russia has given us a glimpse of what the dynamic might be if we go ahead and invade Taiwan.

RS: Yeah. Well, that’s of course the position of the hawks also: let’s show them that they can’t, and let’s get embroiled in that. But leaving that aside, we’re going to wrap this up. I want to say it’s your voice, clearly anyone listening to this, I hope you keep blogging and return to the fray, because your voice is needed. I want to thank Professor Michael Brenner for doing this. I want to thank Christopher Ho at KCRW and the rest of the staff for posting these podcasts. Joshua Scheer, our executive producer. Natasha Hakimi Zapata, who does the introductions and overview. Lucy Berbeo, who does the transcription. And I want to thank the JKW Foundation and T.M. Scruggs, separately, for giving us some financial support to be able to keep up this work. See you next week with another edition of Scheer Intelligence.

Yuval Hariri in His Own Words: What the Vaccines Really Do

Editor’s Note: we are reposting this article linked to by one of commenters. It needs to be widely disseminated.

by Emerald Robinson via emerald

Let’s review what we do know about the new COVID gene alteration therapies that really distinguishes them from actual vaccines, shall we?

- They don’t prevent you from getting COVID.

- They don’t prevent you from spreading COVID.

- They don’t limit the severity of COVID if you get infected.

- In fact, they don’t do anything that vaccines are supposed to do. This raises aprofound question: what are they really supposed to do?

There happens to be an Israeli professor of history who has profoundly influenced Klaus Schwab and the global cartel of trans-humanist oligarchs — and he’s more than happy to tell you what the vaccines actually do. He’s the leading thinker, the arch-guru, of the Silicon Valley dictator set. His name is Yuval Hariri.

At one globalist conference, he explained exactly what the COVID pandemic was being used by the globalist elites to do: “COVID is critical because this is what convinces people to accept, to legitimize, total biometric surveillance. If we want to stop this epidemic — we need to not just monitor people, we need to monitor what is happening underneath their skin.”

Yuval Hariri has said similar things at many other conferences and lectures as well: “Maybe in a couple of decades, when people look back, the thing they will remember from the COVID crisis, is: this is the moment when everything went digital. This was the moment when everything became monitored — that we agreed to be surveilled all the time. Not just in authoritarian regimes but even in democracies. This was the moment when surveillance went under the skin.”

Do you see? COVID is not the “accidental” release of a bioweapon derived from a Chinese bat coronavirus — it’s actually an opportunity for governments and global corporations to create a total surveillance system around the world that will ultimately control every human being.

This sounds like science fiction. It is not. There are secret ingredients in the COVID vaccines like graphene oxide (that the corporate media tells you is a conspiracy theoryof course!) that can transmit data outside the body — like your heart rate.

What do the COVID vaccines really do? They usher in the Age of Total Surveillance.

Professor Hariri explained this new and terrifying reality (that he wants to usher into the world) to the World Economic Forum in 2018 where our corrupt elites embraced the idea that they would be the immortal masters of the world while they enslaved the rest of us in their new “digital dictatorship.”

Professor Hariri is not alone in his depravity — just check out what DARPA is working on. Needless to say: DARPA (and the Pentagon more broadly) is not really in the healthcare business and couldn’t be less interested in “healing bodies” more effectively. This is simply the cover, the excuse, for the radical intrusion into every sphere of human life which can only be called: totalitarian techno-fascism.

Hariri is not really a humanist either— he doesn’t have any love for humanity. Nor is he really interested in the preservation of democracy. He is the psuedo-prophet of a one world government that would enslave humanity forever using a version of communist China’s social credit system to keep the masses under control.

For instance, Professor Hariri predicts a future where the machines we have created have no more use for humans (because of Artifical Intelligence) and so “by 2050 a new class of people might emerge – the useless class. People who are not just unemployed, but unemployable.” Why would we allow such a future? The premise of the question is not something Hariri explains for obvious reasons. Why would he? He’s on the side of the machines.

Technology is going to turn the Davos crowd into gods, and the working class into peasants to be eliminated as so many “useless eaters.” After all, we humans “should get used to the idea that we are no longer mysterious souls.” We are “hackable animals” so Hariri wants you to get ready to be hacked.

The best way to describe Hariri’s worldview is that he is a nihilist — but nihilism doesn’t really capture how dark and dangerous his thinking happens to be: “As far as we can tell from a purely scientific viewpoint, human life has absolutely no meaning. Humans are the outcome of blind evolutionary processes that operate without goal or purpose. Our actions are not part of some divine cosmic plan, and if planet earth were to blow up tomorrow morning, the universe would probably keep going about its business as usual. As far as we can tell at this point, human subjectivity would not be missed. Hence any meaning that people inscribe to their lives is just a delusion.”

People like Hariri who believe that nothing is real and that everything is permitted are the most dangerous people of all — traditional morality to them is simply a construct that only the weak obey. Hariri’s atheism wants to touch the abyss, and summon the darkness. Even his pessimism is pessimistic. For him, life has no meaning. Free will is an illusion. God does not exist. Religions are transparently absurd attempts to create meaning. Truth is a fiction — only power is real. Humanity is not to be pitied so much as controlled by a superior race of the wealthy and the powerful that (no surprise) enjoy paying exorbitant fees to hear Professor Hariri discuss their future as gods on earth.

Yuval Hariri has only one soft spot, and that’s for animals in our food supply. He’s a vegan apparently: “Domesticated chickens and cattle may well be an evolutionary success story, but they are also among the most miserable creatures that ever lived. The domestication of animals was founded on a series of brutal practices that only became crueller with the passing of the centuries.”

“Let’s enslave humanity, and spare the chickens” is a strange message because chickens and cattle are animals that should be spared in Hariri’s view — but then humans are animals too (Hariri says this again and again) but we don’t deserve any sympathy in the final analysis.

One can’t help but notice the obvious self-hatred contained in these elementary philosophical contradictions that any 5 year old child would notice instantly. Hariri is not a great thinker. He’s not even a sub-par historian. He’s the limp-wristed avatar of a globalist cabal (Bill Gates, Xi Jinping, Klaus Schwab, Larry Fink) that seeks to destroy Western democracies in order to rule behind the scenes like so many Wizards of Oz.

These people are, in other words, the enemies of all humanity.

WHO Is Preparing Vote to Strip the US, and 194 Other Nations, of Their Sovereignty

As part of the World Economic Forum’s Great Reset goal, the WHO is aiming to alter a treaty that would give them global control over human health.

The WHO World Health Assembly will vote on the issue from May 22 to 28.

In a new video, The Pulse’s Joe Martino interviews Shabnam Palesa Mohamed, a member of the steering committee of the World Council for Health, who points out that the treaty gives the WHO:

“… an inordinate amount of power to make decisions in sovereign countries as to how people live and how they deal with pandemics, from lockdowns to mandates over treatment.”

In an open letter on the WHO’s pandemic treaty, the World Council for Health writes, in part:

“The proposed WHO agreement is unnecessary, and is a threat to sovereignty and inalienable rights. It increases the WHO’s suffocating power to declare unjustified pandemics, impose dehumanizing lockdowns, and enforce expensive, unsafe, and ineffective treatments against the will of the people.

It’s the usual Marxist one-size-fits-all approach. Everyone will be on the same page and science will cater to GLOBAL political whims.

It will cost millions of dollars or more and money will be laundered by them and their pickpockets.

The WHO appears to want to push the treaty through quickly without public participation and input.

“It is undemocratic, it is unconstitutional and therefore it makes the treaty invalid and unlawful,” Mohamed says. She also made note of the many WHO health policy failures due to their “conflicts of interest.”

It is much worse than we thought. The rule change includes very dangerous amendments – 13 of them. Investigative reporter Leo Hohmann reports that these amendments will NOT require approval by 2/3 of the United States Senate. It’s not called a treaty. It’s amending a treaty we are a part of.

If they are approved (as submitted by the United States) by a simple majority of the 194 member countries of the World Health Assembly countries), these amendments would enter into force as international law just six months later (November 2022). The details of this are not crystal clear.

Our administration is actively destroying the Constitution by making us part of a global new world order.

“It essentially wipes out 194 nation’s sovereignty,” says investigative reporter James Roguski. [category on the road to serfdom]

Mr. Roguski has a website with information at Don’tYouDare.info.

This gives us the one-world government in an instant:

Is President Xi Being Set Up for a Replay of Ceaușescu’s Downfall?

Editor’s Note: This is quite very worrying. Mr. Xi has staked his reputation on so-called “Zero Covid”. Is the West possibly playing this inflexibility to his disadvantage?By persisting in this fallacy, the Chinese President risks losing the support of his population. This reminds us of the fate of Romania’s Ceaușescu. Most admired by his countrymen in 1968, hated and killed in the end after draconian deprivations of the population in order to develop the country and pay it’s debts at any cost. Is the West using the same playbook against Xi?

In continuing with China’s completely rational and totally not suspect “Covid Zero” policy, reports are now coming in that Chinese authorities are building “cages” around some homes.

This week, people living in Shanghai woke up to “green fences that had been installed by authorities overnight to restrict people’s movement,” according to a new report by The Mirror.

People with fences around their homes are not permitted to leave their properties, the report says.

Shanghai has had its 25 million citizens on lockdown for weeks due to a spike in Covid cases in the country. 39 people in the city died of Covid on Sunday, April 24, when the lockdowns began in full force.

Photographs of the green fencing being used to keep people in are making their rounds on social media. Meanwhile, citizens in Shanghai are already protesting and rebelling against the latest tranche of Covid lockdowns.

The Mirror writes that people are “shocked” by the latest step of putting up fencing. Residents had no clue the measures would be taken until they woke up one day to see it.

One foreign national told The Mirror that green fencing “popped up” a couple days ago and that the main gain to his complex was “chained up” three weeks ago.

The foreign national said: “There is a long corridor in our compound, and within the long corridor they put up another green fence three days ago. No one told us the reason it was installed.”

“No one can get out. I feel helpless. You don’t know when the lockdown is going to end. If your area gets fenced off, what if a fire breaks out? I don’t think anyone in their right mind can seal people’s homes.”

One Twitter user, a documentary filmmaker from China, wrote: “We all have heard stories of residents and even entire buildings refusing to go outside for mass testing. Some are fatigued, others fear that being together brings infection risks.”

““Some think sealed-off entrances like this are to separate these folks. The hope being that other residents of a community would not be punished for the lack of co-operation from a few. This might be wishful thinking,” they continued.

Did Germany Really Decide to Deliver Tanks to the Ukraine?

via Moon of Alabama

Did Germany really decide to deliver tanks to the Ukraine?

The German government said Tuesday it will deliver anti-aircraft tanks to Ukraine after facing strong pressure at home and abroad to abandon its reluctance to supply heavy weapons to Kyiv.The decision to provide the “Gepard” tanks, which come from German defense industry stocks, was made at a closed-door government meeting on Monday, Defense Minister Christine Lambrecht told reporters at a Ukraine security conference at a U.S. airbase in Ramstein, Germany. There was no immediate information on how many tanks Germany would deliver.

The announcement marks a notable shift for Chancellor Olaf Scholz, who as recently as last week was still ruling out sending German tanks to Ukraine, insisting it would make more sense for Eastern NATO countries to give Kyiv old Soviet-era tanks already familiar to the Ukrainian military. Scholz promised Germany would then send those countries replacement German tanks.

I find it amusing how many misunderstand this move. First off – the Gepard (Cheetah) is not a tank as the turret has very little protective armor.

It is a short range (5 km / 3 miles) anti-air system on a tank chassis useful against helicopters, drones and low flying planes.

That Scholz decided to offer these, instead of real tanks or armored infantry carriers as the U.S. and the camouflage-Green party demanded, is a nice way out. It guarantees that the Ukrainians will not be able to use them before the war is over.

The Gepard system with its two 35mm cannons is more than 50 years old but has been upgraded two or three times. The Germany army retired their last one of these in 2010. They have since been held in storage.

I remember them well from my time in the Bundeswehr. While my primary training was as a gunner on a real tank, the Leopard 1A3, two people I knew were trained as gunners for the Gepard. There was a huge difference though. It took 6 months of training to become a reasonably good tank gunner. It took 12 month, including hundreds of hours in a simulator, to become a gunner on a Gepard. The commander role required even more training.

The system was excellent for its time but also really complicate. The two radars have various modes for different purposes. One would better use the right one or risk to attract explosive countermeasures. The startup of the turret systems and the handling of their various error modes that could occur were not easy to handle. The tank chassis is also more complicate than the original one. It has an additional motor which powers five electric generators, two Metadyne rotary transformers and a flywheel to handle the extraordinary fast movements of the turret (2.5 sec for a 360°turn).

There are probably less than ten people in the current Bundeswehr who still know how to operate and maintain a Gepard. There is thus little chance to find German crews for them.

If the Ukrainians really want to use these outdated systems they will have to train fresh crews for at least a year. Otherwise those guns will be ineffective and of little use.

My hunch though is that none of these will ever be delivered. The Swiss, who manufactured the cannons and their ammunition, have seen to that:

Neutral Switzerland has vetoed the re-export of Swiss-made ammunition used in Gepard anti-aircraft tanks that Germany is sending to Ukraine, the government said on Tuesday.Germany earlier announced its first delivery of heavy weapons to Ukraine to help it fend off Russian attacks following weeks of pressure at home and abroad to do so.

The Swiss State Secretariat for Economic Affairs (SECO) confirmed a report by broadcaster SRF that it had blocked Germany from sending munitions for the Gepard tank to Ukraine.

Chancellor Scholz likely knew all that. The offer of Gepards is a safe way to relieve the pressure put onto him to send arms to Ukraine. It is an offer of a system that can not be used within the timeframe of the war and for which he can not deliver the necessary specialized ammunition.

Are there still some Lockheed F-104 Starfighter in German storage? If so those flying coffins should be offered next.

Massive Fraud in French Presidential Elections…

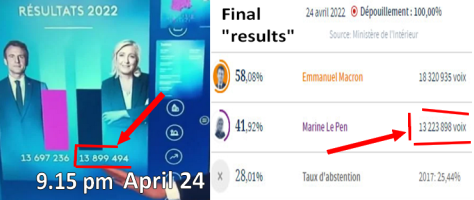

Image above: Marine Lepen had 14 millionvotes at 9.20 pm, and she had only 11 millionvotes left at 10.45 pm. Where did all these votes go?

How France 2, the national French channel exposed the truth (Marine Lepen won the 2022 presidential elections) before being told to pretend it was a “technical error” (while the results where given live and in real-time)…

Successful Hold-Up: 5 More Years Of Jail For France

“Sorry technical error”…

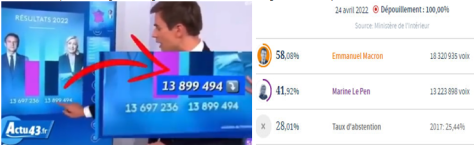

Image below (link to the actual video on TV channel France 2). On the left, the real-time spread of the number of votes counted on France 2 (state TV channel) at 9.15 pm (polling stations closed at 6 pm and at 8pm for few big cities).

- Number of votes for Marine Lepen at 9.15 pm on the 24th of April = 13,899,494

- Number of votes for macron at 9.15 pm on the 24th of April = 13,697,236

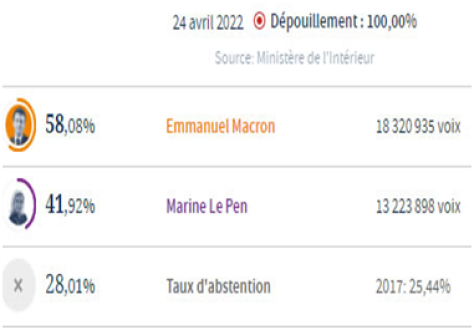

Tied, but Ms Lepen is leading. On the right, the final “results’ according to the ‘ministry of interior’

Number of votes for Marine Lepen according to the ‘ministry of interior‘ (after midnight or next day):

13, 223, 898 votes (compared to 13,899,494 at 9pm). In few hours, she lost 675,596 votes. It also means that on top of this sudden loss, no more votes were counted for her. Welcome to the 4th dimension….

In the same time macron miraculously gained a staggering 4, 236,699 votes! All day long he couldn’t lead over Ms Lepen but in the odd hours after the voting ended, and behind closed doors, he gets 4 million votes…

Even more magical than 2020!

And they showed it on the national channel for all French people to see. Guess what they told the public as an excuse?

A close-up from a different source :

“9:15 pm still tied”. (99% of polling stations closed at 6 pm)

@lequestionniste

“21h15, toujours à égalité”…pic.twitter.com/vSBQIWWh3Q — Le questionniste (77) (@lequestionniste) April 24, 2022

It gets worse, the same national channel, France 2 shows much more votes for Mrs Lepen . She is now at 14, 432, 396at 9.20 pm and still leading over macron. Then the final results from the ‘ministry of interior‘ give 13, 223, 898 votesfor Ms Lepen!

We believe Marine Lepen won this election, by a slight margin perhaps (51% to 49%), but the establishment falsified the numbers.

We also know macron never made it to the second round, but shhhh, they don’t want you to know…

And it starts to be be known, at least in informed circles (while mainstream and fact-censors are trying to silence the truth).

In France and abroad,

Canada,

Live on #radioquebec about #fraude in French elections

The electoral irregularities observed in France on Sunday night resemble those observed in the United States during the last presidential campaign.

Demographics Push China-India-Russia Triple Entente

by

Britain and Russia spent most of the 19th century contending in the “Great Game” over India. Britain built the navy with which Japan beat Russia in the 1905 war. But Britain and Russiafought on the same side in the world wars of the 20th century.

Russia and China fought one war in 1929 and an undeclared border war in 1969, but share common interests against the United States and its allies.

The next strategic alignment among past enemies may bring together two of today’s strategic antagonists, namely India and China. At first glance, this seems improbable in the extreme. India and China have a longstanding border dispute that caused several hundred casualties in a clash in 1967 and claimed the lives of several dozen soldiers in another last year.

But there are three reasons why a diplomatic revolution may occur sometime in the next several years, and two of them are evident from the chart below.

India will have far more working-age people than China as the present century progresses. And the population of poorly educated people in Muslim Asia will equal India and China combined if present trends continue. That presents both an economic opportunity and an existential challenge. This is not a religious issue, but a matter of cultural and educational levels, as I will explain.

The rest of East Asia, meanwhile, will shrink to insignificance. Japan now has 50 million citizens aged 15 to 49 years, but will have only 20 million at the end of the century at current fertility rates. South Korea will have only 6.8 million people in that age group, compared with 25 million today. And Taiwan will fall from 12 million 15-to-49-year-olds today to only 3.8 million at the century’s end.

India surprised the United States by refusing to abandon its long-term ally Russia over the Ukraine crisis. Far from supporting American sanctions, India has worked out local-currency swap and investment mechanisms to conduct trade with Russia in rubles and rupees and invest Russia’s surplus proceeds in the Indian corporate bond market.

In retaliation, US Secretary of State Anthony Blinken waved the bloody shirt of human rights abuse at India, the world’s largest democracy. “We regularly engage with our Indian partners on these shared values” of human rights, Blinken declared, “and, to that end, we are monitoring some recent concerning developments in India including a rise in human rights abuses by some government, police and prison officials.”

India’s Foreign Minister S Jaishankar drily responded that India also has a view about the human rights situation in the United States.

For the first time, India has found itself on the receiving end of the same sort of opprobrium that Washington has directed at China for its treatment of the Uighur minority, and against Russia for its actions in Chechnya and Ukraine. This exchange of unpleasantries stemmed from America’s dudgeon over India’s stance on Russian sanctions, to be sure, but it points to trends in the region that will push Russia, China and India closer together.

America’s humiliating abandonment of Afghanistan left a sink of instability in central Asia. The American invasion sought to destroy the Taliban but ended by restoring it to power, providing at least potentially a base for Islamist radicals in bordering countries including China and Pakistan, as well as Turkmenistan and Uzbekistan.

Russia’s January intervention in Kazakhstan with the firm support of China highlighted the importance of Central Asian security to Moscow, as well as Beijing’s concerns about Xinjiang province. In December 2021, Beijing and New Delhi held virtual summits with the foreign ministers of Central Asian nations during the same week.

If present fertility rates continue, the UN Population program calculates, China’s population aged 15 to 49 years will fall by almost half during the present century, while India’s will grow slightly.

Demographic projections, to be sure, are notoriously unstable, and the UN forecast at best provides a general indication of underlying trends. Nonetheless, the trends are so pronounced and divergent that they will figure into strategic planning by the countries concerned.

Aging populations save for their retirement, and countries with aging populations export capital to countries with younger populations.

China’s main destination for savings is the United States, which for the past thirty years has absorbed most of the world’s free savings, and accumulated a negative $18 trillion net foreign investment position as a result. America can’t absorb the bulk of the world’s savings indefinitely.

China sought alternative outlets for its savings in the Belt and Road Initiative, with mixed results. It has invested heavily in countries with deficient governance and inadequate education.

India is the only country in the world with enough people and adequate governance to absorb China’s savings. China, moreover, better than any other country does the sort of things India needs to be done – namely, digital and physical infrastructure.

In contrast to China, India’s economic takeoff failed at launch. In 1990 the two countries had the same per capita GDP. Today China’s per capita GDP is triple that of India.

India still relies on a railway system built by the British at the turn of the 20th century. Its rural population is 69% of the total, compared with China’s 38%. It requires railroads, highways, ports, power stations and broadband, all of which China has learned to build more efficiently than anyone else in the world.

Despite the natural commonality of interests, trade between India and China remains minimal. China’s exports to India in March 2022 were at the same level as exports to Thailand, and half the level of those to Vietnam or South Korea. That is the cost of Sino-Indian animosity.

Countries that have made the great leap out of traditional society into modernity almost all have fertility rates at or below replacement. Muslim countries with high levels of literacy such as Turkey and Iran will see modest declines in prime working-age population, according to UN forecasts – while countries like Pakistan with low levels of literacy continue to have children at the high rates associated with traditional society.

The UN projections show that the largest growth in prime working-age Asian populations will come from Pakistan and Afghanistan, which exhibit the lowest literacy rates in Asia. Only 58% of adult men and 43% of women in Pakistan can read, according to government data, and the actual level probably is lower than the government reports.

Afghan data are unreliable, but the now-defunct government estimated that 55% of men and fewer than 30% of women could read.

India’s literacy rate, by contrast, is 77% (72% for men and 65% for women), up from only 41% in 1981.

In the Muslim world, female literacy is the best predictor of fertility (the r2 of regression of total fertility rate against the adult female literacy rate is about 72%, and is significant at the 99.9% confidence level). As noted, the issue is not Islam as a religion but, rather, literate modernity versus illiterate backwardness.

The position of the central Asian republics of the former Soviet Union is somewhere in between the pre-modern world of Pakistan and the relative modernity of Iran and Turkey, whose fertility rates have fallen to European levels.

For China, Russia and India, this represents a strategic challenge of the first order. All three countries have significant Muslim minorities, but each country’s circumstances are different.

Muslims comprise only 23 to 40 million of the Chinese population, depending on which estimate one accepts, or less than 3% of the total. Nonetheless, the security threat that radicalized Uighur Muslims presented to the Chinese state was great enough to prompt Beijing to incarcerate more than a million Uighurs for what the government called re-education.

By contrast, some 30% of Russia’s population will be Muslim by 2030, according to several estimates, although data are hard to verify. Russia’s total fertility rate had risen to 1.8 children per female, close to replacement, in 2018, before falling back to about 1.5 after the Covid-19 epidemic, and it is hard to separate Muslim from non-Muslim fertility rates.

Muslims comprise about 15% of India’s population. Their fertility rate has fallen from 4.4 children per female in 1992 to only 2.6 in 2015, still higher than the 2.1 fertility rate among Hindus, but converging.

Twice in the past year, American foreign policy has pushed China, India and Russia into the same strategic corner: America’s humiliating abandonment of Afghanistan, and America’s failure to defuse the Ukraine crisis. The first left the three Asian powers with an intractable mess to clean up. The second persuaded New Delhi that the price of American friendship was to carry baggage that might explode in the not-too-distant future.

For two generations China has cultivated ties with Pakistan, including a $62 billion, 15-year commitment to the China-Pakistan Economic Corridor, a flagship investment of the Belt and Road Initiative. Pakistan’s military flies Chinese J-10 and J-17 fighters as well as American F-16s. Chinese scientists aided Pakistan’s nuclear weapons program, and both countries provided help to North Korea.

But Pakistan may be more trouble than it’s worth to Beijing. As FM Shakil reported in February, the then prime minister of Pakistan Imran Kahn asked China for a $9 billion bailout to prevent a default on loans that mature in June. Pakistan owes China $18.4 billion, according to the International Monetary Fund.

Pakistan is intractably backward, politically erratic and unreliable as an economic partner. China may conclude that a diplomatic revolution is in order – a turn away from Pakistan toward its southern neighbor, which can boast of far greater human capital resources and a strong political system.

Of Pakistan’s 29 prime ministers since its founding in 1947, not onehas completed a full term in office. India has its issues, but it has had an unbroken succession of democratically elected governments for 75 years.

At some point, China may decide to write off its investment in Pakistan and upgrade its relationship with India. And that would turn all strategic calculations inside-out.

The Main Aim of the Ukraine War: Destroying the Unipolar World System

Since the announcement of Russia’s security requirements last December and the obvious fact that NATO wouldn’t confess to its breaking all OSCE security treaties, the question has always been: How will Russia make its security requirements reality. That Russia would perform its own version of an R2P operation was plain when the conditions of genocide in Donbass were announced in November to which Putin agreed.

About two weeks ago, Putin said the following:

“Today, the system of the unipolar world that developed after the collapse of the Soviet Union is being destroyed, that’s what is most important. The main thing is not even the tragic events taking place in the Donbas and Ukraine, because this is not the main thing. Much is said that the United States is ‘ready to fight Russia to the last Ukrainian.’ And they say, and we say, in fact, this is how it is. That is the quintessence of the events taking place.”

Lavrov about the same time said the aim of the SMO is to end the Outlaw US Empire’s hegemony.

Those facts ought to have enormous influence on any analysis of the current situation. Furthermore, two other facts must be added to the scales–China/Russia’s 4 February Joint Declaration and Xi Jinping’s Boao Forum Speech–of the overall Geopolitical equation wherein our Hybrid Third World War’s centered. And all that has bearing on Guterres talks with Lavrov tomorrow:

On April 26, Foreign Minister Sergey Lavrov will hold talks with UN Secretary-General Antonio Guterres, who will arrive in Moscow on a working visit.The focus will be on issues related to the crisis situation in Ukraine, the DPR and the LPR, which has developed as a result of the eight-year conflict unleashed by Kiev against the population of Donbass. The interlocutor will be informed about the progress of the special military operation carried out by Russia in accordance with Article 51 of the UN Charter. It is also planned to touch upon a number of acute issues on the international agenda, including Syria, Libya and the Middle East settlement.

Particular emphasis will be placed on our unwavering support for the work of the UN and the provisions of its Charter, as well as the central coordinating role of the world Organization in world affairs. In addition, the parties will discuss the possibility of developing productive cooperation between Russia and the UN Secretariat.

Somehow a global view of the Big Picture needs to be adopted instead of the Westerncentric POV to which most of us are subjected to. However, this Western saying is very apt: Pride goeth before the storm.

Transnistria Explained from the Russian Side

By Evgeny Norin, a Russian historian focused on Russia’s wars and international politics

The uprising in Transdniester was a monument to human stupidity and idealism

The current crisis in Ukraine, in which Russia has recognized the rebel republics in the Donbass, looks unusual, but this is not a new story for the post-Soviet space. Something similar to the events happening in the Donbass today took place in 1992, and the enclave that then arose still exists.

The unrecognized territory, formally part of Moldova, was formed as a result of a short war, which was simultaneously absurd and cruel. That war contains many parallels with the current conflict – including even the personal stories of many of its participants.

The collapse of the Soviet Union was accompanied by a series of armed conflicts. Some have gone down in history as examples of insane, unbridled violence, comparable only to conflicts in Africa and the Middle East. However, a strange little war in the Transdniester region stands out among them.

This is a barely discernible area on the map, stretching north to south along the Dniester River on the border of Ukraine and Moldova, about 200 kilometers long and only about 20 across. At the end of the Soviet era, it had a population of about 680,000. Before the collapse of the USSR, Transdniester had been a sleepy land where almost nothing happened for many decades.

In 1992, a conflict raged there for several months, when rebels made up of Russians and Ukrainians took up arms against the government of the newly independent Moldova. Despite its very small scale, this war became a kind of prologue for the entire bloody history of post-Soviet armed conflicts.

Transdniester became part of Russia during the imperial era of the Romanov dynasty. The wars between Saint Petersburg and the Ottoman Empire brought the Russian Empire vast expanses of land north of the Black Sea. Under Catherine II, the border passed just along the banks of the Dniester River, and it was then that the future capital of Transdniester, the town of Tiraspol, was built. A decade and a half later, Russia recaptured Bessarabia from the Turks – the eastern part of the ancient Moldavian principality, whose territory formed the basis of present-day Moldova.

These lands lived more or less peacefully as part of the Russian Empire. The roots of the current problem stretch back to the events of 1917. As a result of the Russian Revolution and Civil War, Moldova became part of Romania, but Transdniester remained with the Soviet Union. The USSR assumed the implicit role of collector of Russian imperial lands, and Transdniester was singled out as a Moldovan autonomous region for political purposes. Following the events of World War II, Moldova was annexed by the USSR, and Transdniester was included in its composition.

The problem was that Transdniester was a very specific region for Moldova. Its economic structure was very different from the rest of the republic. Unlike agrarian Moldova, Transdniester was primarily an industrial area. Despite it accounting for just 17 percent of Moldova’s population and very small portion of its territory, by the late Soviet period, its industry provided 40 percent of the republic’s GDP and up to 90 percent of its electricity.

Another major difference was in the region’s ethnic composition. The majority of the Moldovan population were Romanian-speaking Moldovans, related to the their neighbours in Bucharest. However, in Transdniester, the majority of the population was made up of Slavs – Russians and Ukrainians. For obvious reasons, Moldovan nationalism, which came with a revival of ties with Romania, did not find any support in Transdniester at all. In the industrial Russian-speaking and Slavic region, pro-Soviet views remained popular even during the crisis that led to the collapse of the USSR itself.

As long as the Soviet Union remained strong, none of this was a problem. For the USSR, ethnic nationalism was unacceptable. The peoples were fused together by ideology – at least officially. However, by the end of the 80’s, the USSR was torn apart by a variety of difficulties. In particular, the national issue had reemerged with a vengeance. During a time when the USSR was experiencing an array of internal problems, the popularity of Soviet ideas was rapidly losing popularity, while nationalist populism was gaining strong momentum among the peoples living on the outskirts of the USSR.

Armed conflict between Moldova and the unrecognized Transnistrian Moldovan Republic (March 2 – August 1, 1992). © Sputnik / A. Shadrin

The Soviet project had encouraged the creation of a stratum of intellectuals and managerial personnel in national republics, as it was part of socialist ideology, with its internationalist ideas. However, this now made it possible to create turnkey states: under Soviet rule, the USSR’s ethnic republics had managed to rebuild industry and create more or less functioning national bureaucracies. Meanwhile, the national intelligentsia educated by the USSR could adapt its ideology to support the idea of seceding from the Soviet Union.

Finally, another important detail: the Soviet 14th Army was based in Transdniester. Though its complex of military facilities were more akin to giant arsenals than a full-fledged combat-ready contingent, there were enough weapons to arm one. Furthermore, there were many retired officers living in Transdniester who kept in touch with each other and formed a fairly influential ‘corporation’ in the region.

Transdniester ceased to be a quiet picturesque corner of the USSR by about 1989, when Moldova was experiencing a surge of nationalism and ethnic romanticism. The leaders of the emerging state dismissed its Soviet past, on the one hand, but, on the other, were actually part and parcel of the Soviet intelligentsia, with its vague ideas about how states function in the West. Naturally, this also affected their views on how a nation that has just achieved statehood should build relations with its citizens.

The beliefs of these people ranged from sincere fanaticism to a desire to play the national card to score political points. They included, for example, Mircea Druk – who expressed nationalist convictions back in the heyday of the Soviet Union but was, in fact, a typical representative of the Soviet nomenklatura who revelled in the role of a privileged official. Another leader of the Moldovan independence movement, Mircea Snegur, was also originally a party careerist, but the collapse of the USSR opened the way for him to transform himself from an ordinary regional official into the leader of a small and poor, but separate state.

A separate problem was presented by the idea of reunifying with Romania, to which the Moldovans are close in blood and language. Though these views might have been popular in ‘native’ Moldovan society at that time, such a future was categorically unacceptable for Transdniestrians.

It was the extreme radicalism and extreme naivety of the event’s participants, along with an unwillingness to compromise, that led the issue to escalate into civil confrontation, and eventually war.

It all started in 1989, when a draft law was introduced in Moldova on the adoption of the Moldovan language as the only state language, and its transition to the Latin alphabet. This decision was made based solely on the nationalistic feelings of Moldovan ultra-patriots, without any attempts to sound out the public on the issue.

In Transdniester, the situation was particularly difficult. On the one hand, people were frightened by the increasingly harsh nationalist rhetoric, and, on the other, far from everyone in the region spoke Moldovan. A strong sense of solidarity had already developed among Transdniester’s population, and workers from large industrial enterprises and retired military personnel were well united. In the same year, they formed the United Council of Labor Collectives (UCLC), which represented the interests of Transdniester as a whole.

In the summer of 1990, Moldova (now the Republic of Moldova) declared independence. And on September 2, the Pridnestrovian Moldavian Republic was already proclaimed at the Congress of deputies of Transdniester. It was headed by an ethnic Russian named Igor Smirnov – the son of a school principal and a journalist, who had worked in industry all his life. Though he had lived in Transdniester only since the 80’s, Smirnov was the director of an electrical plant in Tiraspol and was already well-known in the region.

Transdniestrians were motivated by several considerations. On the one hand, given the newly proclaimed Moldovan government’s clumsy actions and its rhetoric, in particular, people were afraid of discrimination by nationalists. On the other, many people wanted either to preserve the Soviet way and order of life, or vice versa, wanted financial concessions for Moldova’s most economically important region.

A soldier of the Transnistrian Army marches with a Kalashnikov and a Soviet Union’s belt during the 10th Transnistrian independence ceremony in the non-recognized Republic of Transnistria September 2, 2001 in Tiraspol, Moldova. © Yoray Liberman / Getty Images

However, in Chisinau, Moldova’s capital, they had already taken the bit: the romantics there considered all autonomy projects nothing more than an insurrection staged by mutineers. So, the confrontation took shape.

On one side of the barricade were the Transdniestrians – ethnic Russians and Ukrainians who held pro-Russian or even Soviet beliefs. On the other remained the bulk of Moldovans, who embraced nationalist ideas.

In reality, the situation was much more complicated. Among the Transdniestrians, there were many Moldovans with socialist views, or who simply joined the militia for friends and neighbors. And among the Moldovan security forces, there were many Russians who remained due to career prospects or out of loyalty to the new state.

The Soviet 14th Army, which was headquartered in an ancient 16th-century fortress in the city of Bender, was an important ally of Transdniester from the very beginning. In the chaos that accompanied the collapse of the USSR, it essentially stopped taking orders from Moscow. Though some of the officers hesitated, many actually sympathized with the Transdniestrians, especially those whose families lived in Moldova.

The real war was hampered by a lack of weapons, but there was a huge quantity left over in the country’s warehouses. Consequently, both of the forming sides pillaged the Soviet warehouses. Moldova created its own armed forces, initially on the basis of volunteer detachments and police. In Transdniester, they formed their own militia and Republican Guard.

At first, the Moldovans tried to solve the problem simply. Smirnov was abducted while in Ukraine, probably with the knowledge of local special services. However, the confrontation had not yet reached the level of a real war at that time, and the rebel leader was released after he threatened to turn off the lights in Moldova, since its electricity came from Transdniester.

However, it was clear that real battles could be looming on the horizon. Volunteers from Russia and Ukraine came to Transdniester, often with opposite political beliefs – from communists to monarchists. The Russian Cossacks, revitalized amidst the Soviet collapse, also sent an unusually large number of volunteers who stood out with their archaic uniforms and violent temperament.

The local militia also included many of the kinds of characters who come to the fore precisely in an era of anarchy. The most striking of these was Lieutenant Colonel Yuri Kostenko, a Soviet army officer and Afghan war veteran. He had retired from the army because of his difficult temper to become one of the first private entrepreneurs in the city of Bender by the early 90’s. Amidst the escalating conflict, Kostenko formed his own Republican Guard battalion and became famous as an insanely brave and, at the same time, very cruel man, who paid no heed to his superiors. Opinions about him varied. In Bender, he was seen by some as the city’s main crime fighter and, by others, as its main crime boss. In any case, even his enemies noted his bravery, and even his friends reproached him for his ferocity. He quickly established contacts with former colleagues who helped his squad get hold of weapons. Many detachments were created in a similar way, with officers in the Soviet 14th Army actively participating in the formation of the militia with tacit permission of the army’s commander, Gennady Yakovlev.

In 1990, the USSR was already in its death throes, and war was breaking out in Transdniester. The first blood was shed in the town of Dubossary, which is located in the geographical center of the republic. On November 2, 1990, Moldovan police tried to enter the town and met a hostile though unarmed crowd. One of the policemen lost his nerve and opened fire, and three people died. The police themselves did not expect this course of events, but the killings provoked horror and outrage. The war began to take on a life of its own. Up to that time, recruits had been entering the militia in neither a torrent nor a trickle, but now people in the city went en masse to enlist in detachments.

The Moldovans’ plans were simple and quite logical – to force their way across the Dniester River via bridges and cut Transdniester in two.

Not far from Dubossary, there was a small sculpture on a hill depicting a pioneer playing a bugle. Trenches were dug under this trumpeter, and it was used as an orientation point when shooting. By the end of the fighting, the plaster boy, whipped by shrapnel and bullets, looked like a real symbol of the turning point between epochs.

However, neither side had a regular army, and, instead of a blitzkrieg, both Moldovans and Transdniestrians fought in the trenches for months. This war differed from the trenches of the First World War, however, in that both sides were poorly prepared and lacked heavy weapons, which prevented effective combat. Another notable difference was that it took place amidst beautiful southern surroundings.

In general, many fighters perceived the coming war as a paramilitary picnic. Soldiers and militiamen often came to the front with canisters of wine, sometimes with girlfriends, and enthusiastically photographed themselves in uniform with their weapons. One fighter recalled that huge cherry trees grew in the neutral zone, which the enemies often climbed to pick while exposing themselves to the line of fire. But then they enjoyed the harvest for which they had risked their lives.

Sometimes these picnics were interrupted by truly fierce battles, however. The Moldovans tried to break through the front, while the militia constantly raided the warehouses of the 14th army, taking away weapons and ammunition. Sometimes, the attendants even asked the raiders to tie them up or beat them a little so that they could honestly say the equipment had been stolen from them.

State flags of Russia and Transnistria fly in the wind on the eastern border with Ukraine, on September 12, 2021. © Sergei GAPON / AFP

During the time that these bloody picnics lasted, the USSR collapsed, but that changed little for the combatants. The Moldovan side failed to break through the front around Dubossary. One huge factor was that few people in Transdniester or Moldova really wanted to fight. And while the militias were defending their own homes, the Moldovans lacked such motivation. There was no serious reason for this war, and few people wanted to die in it. As a result, the fighting was sluggish.

By the summer of 1992, the Moldovans decided to change the direction of the offensive. This time the target was the city of Bender. Unlike nearly all of the rest of Transdniester, this city is situated on the west bank of the Dniester, so the river did not need to be crossed. On the contrary, the bridge across the Dniester was behind the city’s defenders. In addition, it is a large city by local standards, with more than 140,000 inhabitants, and the key base of the 14th army was located there, which meant it had both an arsenal and a strong contingent of Transdniestrian supporters.

All of these reasonable considerations pushed the Moldovan military to a general battle. However, everything did not go according to plan, and the ministers and generals subsequently placed responsibility onto each other. In the end, many tried to pin the blame on President Mircea Snegur, who, in turn, claimed he knew nothing about the fighting.

Oddly enough, the Moldovan police department continued to work in Bender, mostly defending themselves. However, on June 19, they arrested a major of the Transdniestrian Guard, who was carelessly moving around the city accompanied by only a driver. A spontaneous battle broke out in the city and the police station was surrounded. At that moment, a group of Moldovan troops was approaching Bender, while graduation parties were just taking place in city schools. Later, Moldovans were reminded of the extremely inopportune timing of the attack.